What are some of the things you consider essential in your life? Lots of people would rank their morning cup of coffee pretty high on the list, right? But dig a little deeper for a moment and think about some of the essential things that you might sometimes take for granted – not just food, water, shelter, etc, but a sense of dignity and purpose in your life, as well as a feeling that there are opportunities available to you. That’s something that we don’t just crave, but that we need to really thrive.

Now what if you combined those two things? Sounds like a recipe for perfection – and it’s exactly what Amy Wright, founder of Bitty & Beau’s Coffee has done. So what does coffee have to do with dignity, purpose, and opportunity? Well, it depends on who’s serving it up: at Bitty & Beau’s all of the employees have intellectual and developmental disabilities, and they, as well as the shop, which now has multiple franchised locations, are doing great.

“A Fire Is Ignited in You”

Amy Wright and her husband, Ben, feel extremely lucky. Their four children, two of whom (Bitty and Beau) have Down Syndrome, and one of whom is living with autism, are the light of their lives. Not only that, but Wright’s children have also changed the trajectory of her life, and have been the driving force behind her passion to make a difference. Wright put it simply and beautifully in her acceptance speech when she was named the 2017 CNN Hero of the Year: “I would not change you for the world, but I would change the world for you.”

And she told guideposts.org: “I just feel like they’ve made us better people. They’ve made us care about things that we didn’t even know about before. It’s just like an appreciation for humanity. It’s far beyond people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. It’s caring about every life and the value that every person’s life has. When you watch your child go through being marginalized, being discriminated against, being overlooked, a fire is ignited in you. And you start wanting to change the world, not just for them, but for any other group of people that’s ever been marginalized that way.”

But that’s not to say it’s been easy – nothing worthwhile ever is. As Wright told CNN, “When Beau was born, we were thrust into the world of special needs. So, we’ve been trying to advocate in different ways since then, and that intensified after (we had) Bitty. But it’s so hard to get people to change their perceptions. It felt like we were swimming upstream. People are scared of what they don’t know, so that’s why we’ve decided to live out loud and to show people what our lives are like.”

And Wright and her husband didn’t stop at advocating for their own children. When they found out that anywhere between 70% and 80% of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are unemployed, they were shocked, and wanted to include as many people living with IDD as they could in their quest to change perceptions. So Ben began hiring people with IDD in his office, and Amy started a nonprofit to help people with IDD get jobs – but she “had hundreds of people who wanted jobs and could barely find an employer who would even give one of them an interview.” But Wright didn’t give up, she simply had to take matters into her own hands and become the employer herself.

“When Your Passion and Your Purpose Collide”

So what would be the perfect venue for the Wrights’ vision to not only create jobs for people with IDD, but also change perceptions and bring communities together? “It hit me like a lightning bolt: a coffee shop!” Wright said. “I realized it would be the perfect environment for bringing people together. Seeing the staff taking orders, serving coffee – they’d realize how capable they are.”

The only issue? The Wrights had no experience running a retail business – but again, Amy wasn’t going to let anything stop her. She talked to people she knew who were coffee roasters and spent hours on the internet researching how to open and run a coffee shop. “We just started drinking from the fire hose. We just had a lot of faith that it would work out. I just believed that it was what we were supposed to do with our lives and it became our passion. When your passion and your purpose collide like that, there’s no stopping you.”

And thus the first Bitty and Beau’s was opened in 2016 in Wilmington, North Carolina (although it was originally just Beau’s Coffee until Beau’s 12th birthday wish was to see his sister’s name “put up in lights, too”) with 20 employees who trained for two weeks to get ready for their new positions. They didn’t need any experience, just a willingness to learn and a dedication to the vision of the shop. The rest Wright took care of, becoming impressively adept (especially considering her lack of retail experience) at matching the right person for the right job.

“We just kept role playing and practicing until we figured out, ‘Where is this person most comfortable? Where do they feel confident?’ … Hiring people with IDD, it’s really no different than hiring people that are typically-developing. Everybody has talent, everybody has skill sets. It’s identifying what those talents are and finding out the way that you can plug them into your business.”

“Radically Inclusive”

The first Bitty & Beau’s location was an instant success, with lines out the door; today they have 23 franchised shops across 12 states, and they have partnered with corporations to open shops in their world headquarters. They also have a range of merchandise for sale, including mugs that say “radically inclusive” and hats that say “not broken.”

So what’s the secret of Bitty and Beau’s success – why are their coffee shops so popular in a world that can feel a bit oversaturated with coffee shops? It’s partly that people are eager to support the mission of the shop, but it’s also the unique warmth that their shops exude: there’s a greeter at the door (who once upon a time gave hugs), and the staff uses playing cards (instead of the usual mangled name on a cup) to identify customers’ drinks, as well as to help the employees practice their numbers.

Wright made it clear to CNN that the admirable mission behind the shops is one thing, but her employers are what make things work like “a well-oiled machine”: “Every single day, people say, ‘You made my day. Thank you.’ There’s something so pure about our team. They genuinely are happy that you’re there, and they make you feel that way. That’s a feeling most people don’t get anywhere that they go, and I think it’s what draws people back.”

“It’s More Than a Cup of Coffee – It’s a Human Rights Movement”

The profits from Bitty & Beau’s go to Wright’s nonprofit, Able to Work USA, but what the shops are achieving is much more than financial support. First, the jobs that they supply to their local community are about more than just employment. As Wright points out, “Having a workplace that makes you feel proud of yourself and gives you a sense of community is something we all want. For our employees, I feel like it’s the first time they’ve had that…It’s given them purpose and a sense of being valued in ways that we take for granted.”

Second, the goal of Bitty & Beau’s is not to tug at your heartstrings, or make customers feel like they’re being “charitable.” Wright wants her shops to build bridges, so what she hopes is that customers who frequent Bitty & Beau’s will become so comfortable and familiar with people with IDD, that their disabilities are not what they notice or think of when they interact with them. “Creating this has given people a way to interact with people with disabilities that (they) never had before,” Wright told CNN. “This is a safe place where people can test the waters and realize how much more alike we are than different. And that’s what it’s all about.”

So Bitty and Beau’s goes from strength to strength, breaking down walls as they open up doors to new shops: franchises have just opened in Bethlehem, PA, Charlotte, North Carolina, and New Athens, Georgia. But Amy Wright knows she can’t hire every person with IDD in the country – but then, the goal is for her to not have to do that. The goal is to change minds and make sure everyone is valued and given opportunity, no matter how they are abled. After all, it’s all about respect: “We always say, it’s more than a cup of coffee. It’s a human rights movement; the coffee shop is just a vehicle for making that happen.”

We’ll leave you with Amy Wright’s words to guidepost.org, which seem to perfectly sum up what one radical coffee shop franchise is achieving: “We can’t open enough coffee shops to affect the unemployment rate. We’ll keep trying, but what we can do is change the way people see people with IDD. Once people value people with IDD, the way they do typically-developing people, then all the opportunity will just flow. We hope the big takeaway when people learn about us or experience the shop is that they go away thinking, ‘You know what? That person with Down syndrome, their life has just as much value as mine does and I need to find a way to include and accept them in my society.’”

If you want to know more, find a location, learn about franchise opportunities, or snag some Bitty & Beau’s merchandise, head to their website.

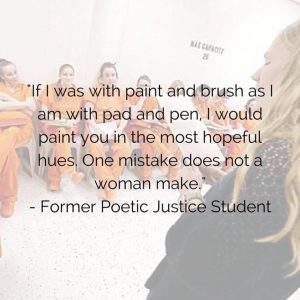

As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”

As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”