When is a fashion brand about more than being fashionable? And what do scarves and leather bags, beautiful as they might be, have to do with empowering women and lifting them out of poverty? These questions aren’t riddles; in fact, they can be easily answered by checking out one brand: Barrett Ward’s ABLE, an ethical company that sells clothing and accessories, and is deeply committed to employing and empowering women as a solution to the plague of poverty, here and around the world. This deep commitment to employing and empowering women is actually the whole reason for the existence of ABLE, and the products it sells are a (very lovely) means toward achieving that end. According to Ward, “For us, empowering women isn’t a marketing tactic. It’s the solution to ending poverty.”

So how did someone who describes himself as “the least fashionable person in the office” make the decision to start a fashion company, and how is ABLE changing the lives of women, as well as changing the game when it comes to responsibility and transparency in business?

“One Inevitable Step After the Other”

According to Barrett Ward, founder and CEO of ABLE, “I didn’t set out to start a fashion company – my team would resoundingly agree that I’m the least fashionable person in the office. This journey is one that found me.” And Ward’s road to building his fashion brand has certainly included some long journeys: while working in the corporate world, Ward ended up on a trip to Peru, a trip which would alter the course of his life. “I was struck by the feeling that I was missing the entire point of life, and I began to grapple with the chasm between the life I lived and the poverty I witnessed. This started a journey of self-discovery that led me to the nonprofit world for the next 5 years…I don’t actually remember making a decision to jump in and do something. Instead it felt like one inevitable step after the other. I stumbled into that trip to Peru, and from there I wanted to continue my travels around the world to see what might be next.”After some more travels, what was next was marriage and another long journey, this time a move with his new wife to Ethiopia. It was there that the idea for ABLE found him: he and his wife were living in close proximity to the commercial sex trade that is very common in that country, and were constantly seeing what poverty can force vulnerable people to do. “Young women having to sell their bodies to make ends meet is just unacceptable. You either have to ignore it completely, or you have to do something about it,” according to Ward.

So he met women who were struggling to break free from that life, and listened to their stories: “I met one woman who had gone into prostitution to save her sister from breast cancer, and I felt compelled to find a sustainable solution for these women who were actually making heroic sacrifices, ones I couldn’t imagine having to make, for those that they love.” The women he spoke to agreed that they were interested in a “sustainable solution”: they weren’t interested in charity, they were looking for opportunities.

According to Ward, “If you’re going to be serious about solutions to poverty, then you have to create jobs, and you have to do so for women. That is a socially scientific fact. So that’s really where we started. It wasn’t this grand vision of changing the world. It was simply a few women saying ‘we need a job.’” The idea that the women came up with? Making scarves.

“Taking Care of the Person Next to You”

Ward and the women he met were ready to flip the script – on the fashion industry, on the expectations of these women, on their impoverished circumstances. As Ward explains, “In Addis Ababa, scarf-making is a big industry, but it was largely male-dominated. So we trained women how to make scarves and sold them during the holidays. In just 2 months we sold over 4,000 scarves. We were blown away, but we knew we were onto something.” So, before he knew it, and without any previous fashion experience, “we had become a scarf company.”

Since its beginnings in 2010, that little scarf company has grown and evolved, and is now a full-blown lifestyle fashion brand, offering not only handwoven scarves, but also leather goods, shoes, jewelry, and apparel that are made in the U.S., as well as in partnership with manufacturers in Ethiopia, Mexico, Peru, and Brazil. Ward has brought ABLE to the United States, setting up headquarters in Nashville, Tennessee, where he continues to run it as a truly woman-led company, with women making up 64 out of the 67 employees at HQ.

For Ward, expanding in this way is the key to keeping his business sustainable, so they can stick to their founding conviction that “Creating economic opportunity for women is the key to ending generational poverty around the world.” After all, as Ward and ABLE have moved on from simply being a way to help three women escape the sex trade, Ward has learned more and more about how truly transformational empowering women can be. He points out, “A woman spends an estimated 80% of her earnings on her family and community, whereas a man only spends 30 to 40%. So that means when a woman is empowered, there’s a greater investment in children’s health and education. The impact that it has on poverty is exponential, so this is the first data that drove us as a company to invest in women.”

But there’s more than just cold, hard data here. Ward sees first-hand, every day, how ABLE is making a difference: “I could tell you 5,000 stories, but a couple of weeks ago a young woman that came out of heroin addiction said, ‘Hey look at my new glasses. I’ve never had glasses before because I’ve never had health insurance. And I’ve never had vision insurance.’ Those kinds of moments just break your heart and also fill it up.”

For Ward, it’s all about “taking care of the person next to you…And even in that kind of cheesy but seemingly obvious way, when a loved person leaves your office and loves someone else well, that’s not cheesy. That seems factual and strategic to me. So we really believe in starting in our core company. We have a ten thousand dollar contribution to women that are experiencing infertility; we have a ten thousand dollar contribution to women going through adoption; we have fully paid health care, and every woman is an owner in the business. All those little things established for us early on made a statement within our budget of who we want to be.”

“It Feels Right”

As he has gotten more involved in the fashion world, Ward has learned that it has a distressing dark side, and that, for the hidden women working in this industry, just being employed is not necessarily positive or empowering. Says Ward: “The fashion industry itself is broken. It is estimated that fashion employs more than 60 million people – 75% of whom are women. It’s one of the largest industrial employers of women in the world! Yet less than 2% of fashion’s workers earn a living wage. That’s nearly 45 million women unable to afford the basic needs of themselves and their families.”

So, in the last few years, Ward has decided to do something innovative through his work with ABLE, and it isn’t developing a new fashion accessory or other product: he’s decided to bring radical transparency to the fashion industry, and to hold it accountable for the way the women involved in it are treated. After all, while the whole purpose of Ward’s company has been to empower women and lift them out of poverty, many big players in the fashion industry are simply exploiting them.

What Ward has realized is that the industry isn’t going to change itself, and that governments aren’t going to step up and hold it accountable, so, for him, the only way to start making things right is to rely on consumers to demand better. To this end, he has decided that consumers need all the facts about the companies they are buying from – and he’s started with his own, publishing not just the highest wages of employees, or the average salary, but the lowest wage they pay their employees around the world, as well as a sort of nutritional facts sheet of their wages and practices.

And what does he say about the flaws in his business that this transparency has uncovered? He makes it clear that, while perfection would be great, progress is what really matters: “I want to run our company putting out into the world that you don’t have to be perfect before you can be honest. And so we’ve put that out there with publishing wages. It feels right. When you’re aligned with your ethics, you’ll run the business that makes you happy and makes you feel at your core that you’re living out your mission.”

Ward is also working to help other businesses evaluate the practices of their supply chains, specifically in how they affect the women working at every level. He’s created an auditing system called ACCOUNTABLE: “A couple years ago, we were going through other auditing platforms and realized that there was a gap in the market for an assessment tool that specifically evaluated the impact on women, so we started to think about creating our own…[T]he only way consumers can protect these workers is if they have concrete information about how much the lowest-paid workers are making. We wanted to create a nutritional label of sorts, where consumers could see clear data on those making their products.”

From helping three women find jobs making scarves, to becoming a leader in the push to bring accountability to an industry that is known for exploiting women workers, Barrett Ward is not just changing lives, but hopefully changing what consumers expect from their purchases, so we can begin to make a dent in the massive problem of global poverty. He is choosing honesty and transparency as a way to take care of the most vulnerable in our world, and giving consumers the chance to protect the people making their products. In the words of Ward, “By doing this, we hope to break the seal of the secret that is keeping women oppressed in fashion manufacturing, putting us on the path to long-term sustainable change once and for all.”

Check out ABLE’s website for more about their mission and products, and if you’re a business owner, consider getting involved in their #PublishYourWages movement.

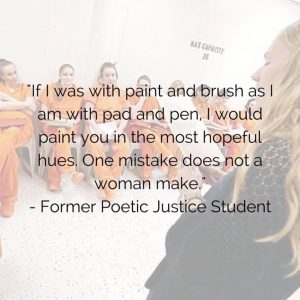

As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”

As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”