It can be hard to tell an eager young person that they’re too young for something. There are some things that just have to wait, though, until adulthood: driving, staying out as late as you like, getting your own credit card. But how about giving back to your community? Can you be too young to dedicate yourself to service? Grace Callwood, founder of the nonprofit We Cancerve, which raises money, gives out grants, and provides fun experiences for sick, homeless, or foster children, has the answer to that question, and it might just give everyone hope for the future.

“Let’s Give Them Our Food!”

According to Grace Callwood, “There’s no age limit on service.” And she has certainly proven that: celebrating 10 years of working hard to help others would be an achievement for anyone, but when you’re not even old enough to drive yet? That’s an astounding achievement. Grace, who is now 16, started We Cancerve when she was only 7, but she has been focused on giving back for as long as she can remember.

It all started when Grace was only 2 years old. She was hospitalized with a minor illness, and recalls how the toys the hospital provided were a bright spot for the children there. The most fun, she remembers, was a red wagon they could ride around in – the only problem was, there was only one. So, when Grace asked for one for herself from her parents, she made sure to ask for one to give to the hospital, as well.

And so Grace got her first taste of giving, and she kept going from there, making each of her birthdays an opportunity to bring joy to others. For her third birthday, she had a princess party, like many children; but unlike most children, she requested that her guests give gifts to the hospital. The next year, after hearing that the Maryland food bank was running out of supplies, she excitedly turned to her mother and said, “Mom, let’s give them our food!” Instead of raiding her pantry, though, Grace ended up gathering donations for the food pantry for her fourth birthday.

Grace would most likely have continued on in her efforts to make the world a better place in whatever ways she, as a child, could do, but then something happened that changed everything, and led her even further down the path of service.

“I Could Relate to Them…I Could Really Help”

When Grace was 7, one of the most devastating things that can happen to a child and their family happened: Grace was diagnosed with stage 4 non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. According to her, “That was completely new to me, I mean I was 7, I had just gotten into first grade and I had no idea what cancer was or what it meant. It was a very fast process and I just kind of had to go with it, because I had no choice.”

While doctors worked quickly to remove the cancer from Grace’s body, her aggressive illness meant that she would have to be on chemo for the next three and a half years, and the cancer and treatment took a toll on both her body and her young life. “Being diagnosed came with tons of changes,” she said, describing how she has always loved school, but was unable to attend first and second grade; she couldn’t see her friends, she gained and lost weight, and she lost her hair 5 times.

But even in the midst of all this, Grace remained as deeply compassionate and as committed to helping others as she had always been. When a family friend shared a story of a local family who had lost everything in a fire, she made up her mind to give them the brand new back-to-school clothes that she would not be needing.

She was touched by their situation: “They had two little girls, and all I could think about was how they had lost everything, and they had just entered homelessness and this super scary and sad situation – and I had just entered sickness, this also different super scary, sad situation…it just made sense to me…my mom delivered the clothes to them because I was too sick to go, and when she told me how happy the girls were, I knew that I wanted to keep doing more work like that, because I’ve always loved to make people happy. I definitely wanted to keep that going – and I knew that they needed it, especially because they were my peers and I could really relate to them.”

Soon after, Grace went on a Make-a-Wish trip to Disney World, where she was given some much-deserved fun, and a whole lot of toys. Recognizing that she had more toys than she needed, Grace donated the toys she had received to the same transitional housing program that the girls who had been affected by the fire were staying in. Her generosity even made the news – but she didn’t stop there. Next was a lemonade stand that raised over $600 for charity, and, for her, “That was a huge indicator that I could really help a lot of people because people believed in me.”

Grace, still only 7, and still battling cancer, knew what she wanted to do next, although it took a little bit of persuading on her part, and, eventually, some help from her mom and her grandma to formulate her idea. “When I first brought up the idea of wanting to start an organization to my mom, she was initially against it. I mean, I was 7 years old, I was in first grade, and I was fighting the battle of my life. She was like, that’s nice, but you have to get better first! But I kept pushing for it…and over time I was able to – well, just not stop pushing!”

“Happiness Shouldn’t Have to Wait”

As Grace pointed out, “I was a sick kid at the age when most people get passionate about things. This community service is what I did.” So there she was, at age 7, the leader of the nonprofit We Cancerve, which is founded on two main principles, the first of which is “Happiness shouldn’t have to wait.”

For Grace, this means that vulnerable children who are sick, experiencing homelessness, or living in foster care situations are also entitled to joy in their lives – and We Cancerve works hard to make that happen, reaching more than 23,000 children to date. They give out grants (so far more than $14,000) and in-kind donations (worth more than $300,000) to organizations that serve these children; Grace herself, according to We Cancerve’s website “has been awarded more than $140,000 in national and global prizes for her service work, and she’s raised more than three times as much in in-kind and individual cash donations.” Not only all that, but We Cancerve also runs their own programs meant to enrich young people’s lives.

Grace’s founding project with We Cancerve, for example, is Threads of Hope, which donates new back-to-school outfits to kids in need, just as Grace had done when she was 7. Since then, they have added projects that bring fun to children who are experiencing illness or other hardships, like their Beach in a Bucket and Eggstra Special Easter Bags-kits. Both of these projects not only bring the magic of the beach or Easter morning treats to vulnerable kids, but they also involve other young people in collecting donations and stuffing buckets and bags, teaching them about the value – and joy – of service.

We Cancerve has a very long list of grants they have given, as well as projects they have branched out into, like a relatively new venture into creating libraries for children (for a complete list, check out their website!). Grace’s favorite, though? Camp Happy, a free, 4-week camp for homeless and foster children offering themed daily programs with a camp carnival as a finale. “We were the first organization to make a camp for homeless youth in the country,” Grace proudly told me. And the twist of this camp? It’s created by youth for youth and is run (in a 1-to-1 ratio) by counselors who are all under the age of 18.

In fact, Grace launched the camp when she was just 10 years old. She’s proud of the fact that they run it on a very small budget, and involve the kids who participate in making things for their camp carnival. But it’s the reaction she gets from the participants that really keep her going. She recalled one girl who attended: “It was our first year of Camp Happy, and I was only 10. This one camper was 16 – she was way older than me! She was moody at times, but would sometimes participate. At the end, though, she said that Camp Happy was the most fun she’d had in 3 years!”

“We See the Bigger Picture…We Aim Straight for the Issue”

The fact that young people are not only the recipients of We Cancerve’s generosity, but also the force that drives their programs brings us to the other founding principle of We Cancerve: “There’s no age limit on service.” Grace’s organization is invaluable to the children who benefit from its grants and programs, but it is also a powerful force in the lives of the young people who volunteer for it. “We Cancerve makes it easy to get kids into community service,” according to Grace.

The organization itself is run by a board of advisors made up of youths ages 8-18, who serve one-year terms. They are backed by an adult board of directors, but Grace is clear that they come up with the ideas. Why have a whole board of young people running an organization? According to Grace, “I like the way young people think. We see the bigger picture, we aim straight for the issue. I wanted this organization to be about kids helping kids. We know what kids focus on.”

“Ask Grace, She’s in Charge!”

So how does someone so young take charge so successfully in the way that Grace has done, what does she want us to know, and where is she headed? “I’m used to being the youngest person in the room,” said Grace; not only she has been mentoring 13, 14, and 15-year-olds for a while now, but she is also a popular public speaker and a strong leader who can hold her own when adults doubt her youth-run organization.

“People struggle to understand – parents sometimes assume our parents are doing the work, but then they realize. When people go to my mom she says, ‘Ask Grace, she’s in charge!’… How do I have so much confidence? I know I’m justified, I have the credentials to be heard. But I had to practice and step out of my shell. Maybe it came from learning to talk to doctors when I was little. It’s a bit intimidating sometimes, but I know what I’m talking about.”

Grace, though, made it clear that she doesn’t see We Cancerve as “as a one man show. I do shy away from the spotlight sometimes and my mom says, ‘People are here to see you – you have the vision.’” And while it is clear she is the shining star of her organization, being honored in multiple ways, like with the Peace First Award (at age 10!) and being named the 2019 World of Children honoree, for her, the best part of being head of a nonprofit is seeing everything come together and watching her team succeeding.

It’s not all smooth sailing all the time, of course. Running a nonprofit at such a young age comes with sacrifice and frustrations. She admits that she has lost friends along the way because she’s so busy, and she has to deal with assumptions about her and a lack of understanding from people on the outside. But what’s more important to her – and what can really be frustrating – is getting people to understand the young people that her organization serves.

“What we really need to do is dive deep into research. We need to look at how and why youth are ending up where they are. Race, sexuality, bad living situations can all play a part, and I can understand that. People can become homeless in the blink of an eye, and homelessness can cause issues at school, which can set kids up to just be part of the school to prison pipeline.” It’s true that, according to many studies, kids who experience homelessness are much less likely to complete high school (which, in turn, makes them much more likely to experience homelessness as adults), and are much more likely to be harshly disciplined at school.

Grace has a vision, though, for the future, and her own thoughts on how to move us forward to a more equitable world for all children. “We all need to take a step back and learn,” she said, “We can bond over giving back. All that other stuff doesn’t matter.” We Cancerve is also now addressing systemic racism and the interconnectedness of homlessness and youth vulnerability with race. According to their website, “Black lives matter. Black children’s lives matter. Black homeless youth lives matter. Black foster care youth lives matter. Their lives matter so much that I’m pledging $8,460 to be dispersed over the next four years for rapid rehousing, mental health services, education and vocational services, and emergency services to Maryland-based nonprofits with proven records of servicing mostly Black homeless youth, and Black foster youth who are aging out or are aged out of the foster care system.”

Her organization is certainly giving back to the most vulnerable among us – children. It is also helping to teach the next generation that service can be life changing for both the recipients and those who are doing the serving. And Grace herself? What does the future hold for her? She hopes to head to Howard University in a few years and study political science, and is thinking about trying for elected office afterwards. “I want to make a longer lasting impact. If I can help change policies, then grassroots organizations won’t have to do the heavy lifting,” she said. If we can look forward to Grace Callwood advocating for us and our children, then the future certainly looks bright.

If you’d like to help We Cancerve, you can donate here.

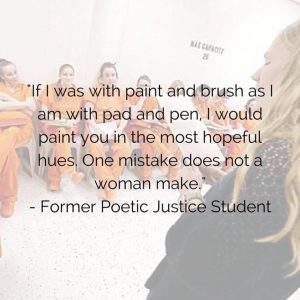

As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”

As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”