I think many of us have suspected all along that English teachers change the world. You often meet people in that profession who have a certain passion for making a difference in the lives of their students. Sometimes, though, you meet one who really goes above and beyond the call of duty. Ellen Stackable, co-founder of the nonprofit Poetic Justice, is without a doubt among them. Her organization, which turned 7 this past March, brings creative writing classes to women in prison – but it’s so much more than what that simple sentence conveys. Poetic Justice offers a safe space for women who have never had the benefit of a safe space, and gives them room to work through trauma on their own terms and discover just how much they are worth as human beings.

“How Can This Be?”

Ellen Stackable, who has been an English teacher for more than 20 years, grew up knowing the power of stories and that the world isn’t always a fair place. She grew up in Colorado, where according to her, “my mother was a school social worker in some of the worst schools in Denver, and she would come home and just tell stories about it, so I think I just grew up hard-wired for social justice because of her.”

Stackable herself would go on to teach creative writing and literature, but did not forget the lessons of her mother. The written word was a way to bring change to people from within, and eventually she would decide to find a way to bring creativity and social justice together. According to Stackable, “I’ve always felt really strongly that writing is a powerful outlet and tool for healing and processing. So when I was working on my masters degree, I ended up down this rabbit hole of research about incarcerated women in Oklahoma, and not growing up here, I was just aghast…The more I read, the more I found out, the more I thought, ‘How can this be?’”

What she found out was that her adopted state of Oklahoma has the highest rate of female incarceration in the country; in fact, the state incarceration rate for females currently stands at 157 of every 100,000 inhabitants, which far exceeds the national average of 57 people incarcerated for every 100,000 members of the population. Native women are incarcerated at triple the rate, and African American women at double the rate of the population.

But, for Stackable, it’s not just about the astronomical numbers of women being put behind bars in one state. It’s about our cultural expectations of women, especially certain women, and how gender can play a part in enforcing certain laws. “If you’re poor and from a small town, you’re at a huge disadvantage. You are much more likely to get a harsher sentence and to be sentenced…I think it’s probably a series of complex cultural expectations for women…it just seems like in general people are more forgiving of men who are felons than they are women. Kind of like a woman should know better.”

Stackable cited some fascinating and disturbing examples of how she has seen the law applied to certain women. Not only does she point out that the women Poetic Justice works with – and women in prison in general – are often living with childhood trauma and “a lot of times the charge they have is not even something they have done, but someone they’re with has done it,” but the laws seem to be enforced in a very gendered way.

For example, one 19-year-old woman was sentenced to 30 years in prison in Oklahoma for “failure to protect” her child from the abuse of her partner, while her partner was sentenced to only 2 years. In another instance, a woman was pulled over and, because she didn’t have her children in carseats, was told should could either go to county jail for 30 days on the spot and lose her children in the process, or face an uncertain outcome at a trial; she chose not to give up her children and ended up with a felony child abuse charge.

So where can we even start when it comes to these distressing statistics and stories? For Stackable, after going down her “rabbit hole of research,” “I started thinking, well, maybe I could do something. I started looking for a way in.”

“It Takes Tremendous Courage to Tear Open That Scar”

Ellen Stackable eventually found her “way in”: “I finally ended up… [working] with a spoken word poet at the Tulsa County Jail, that’s kind of how we started.” Stackable and her poet partner led spoken word poetry classes, but eventually Stackable would transition to classes in what she calls more “therapeutic and restorative writing.” According to her, “I think spoken word is very powerful, but it’s also kind of like shaking up a bottle of soda and releasing it. It’s fine if you’re there to help pick up the pieces later on. But we really felt like we needed to offer more, almost like, think about the bumpers on a crib! How could we help them so that when we’re not there they could still process.”

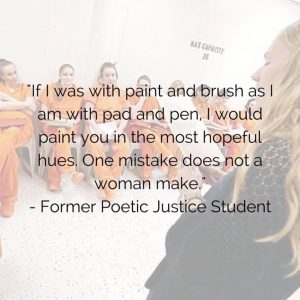

What Stackable really wanted was to move away from the more “confrontational” spoken word performances and move to classes that felt “welcoming,” where the women write their pieces, share by choice, and then ask for either questions, comments, or just silence. “Everything we do has what educators call ‘the hidden curriculum.’ So there’s the curriculum, and that’s the outside part of what you’re going to do in the classroom, and the hidden curriculum, it’s kind of like an iceberg, it’s bigger underneath than it is on top. And our hidden curriculum is that everything we do from the moment we walk in to the moment we leave has this message of you are a person of worth and you matter in this world.”

While, as of my time speaking with Ellen Stackable, the program is still operating remotely due to the coronavirus pandemic and restrictions on volunteers entering prisons, when in-person classes are up and running, they are not, as Stackable says, like “a normal class.” “We go in as facilitators, we don’t call ourselves teachers, and the idea is to really kind of demolish the hierarchy that the women have always been at the bottom of. So we sit in a circle, they make the rules for making it a safe space, and we write with them when they write. It’s really an exploration. We use poetry because there’s no rules to poetry and it’s so forgiving. It’s like group therapy….I think it takes tremendous courage for them to go back into their pasts because almost all of them have very traumatic childhoods, and to go back, and in a sense tear open that scar to find healing, I think takes a lot of courage.”

“Hope, Voice, Change”

For each class, Poetic Justice gives the participants both an entrance survey to get a sense of who they are and what they want out of the class, and an exit survey to see how the class affected them, as well as how they felt about the class and if there is anything that could be improved. The first thing that Stackable found from the exit surveys was that the women all wanted more classes!

And it’s no wonder: the program seems to have an extraordinarily positive affect on their lives. They are instilled with a sense of agency that perhaps many of them had been denied in earlier life. They end each class in a circle, holding hands and repeating “I have a voice, I have hope, I have the power to change,” and they end each 8-week session with a booklet of all of the participants’ poems, a graduation certificate, and the words “Now you’re a published poet.”

The difference in the participants’ lives is actually visible and measurable: Stackable has been working with the Book Research Center in Oklahoma to use her entrance and exit surveys to measure the increase in “hope, agency and positive affect” that Poetic Justice has. And, according to Stackable, “We see a significant change in the end…in so many ways. We see them go on to further education, they finish their GEDs or even go on to do college classes. We see them reuniting with their families, by sending them letters and actually telling them, ‘I’m doing something that matters now. I published these poems.’ We see them become leaders within the prison for good. They are becoming tutors in the GED program…when we’re in the county jail, where women come and go a lot, what the correctional officers tell is us is that ‘It’s always calmer when Poetic Justice comes!’”

Stackable gave a powerful example of one of her students who has been part of the classes from the beginning. Jax, a gifted writer, is serving a life sentence, but has chosen to dedicate herself to the other women she is serving her time with. For example, after learning the story of Cody, a fellow prisoner who had been blinded by her father, and who wanted to get her GED but was told she couldn’t because of her blindness, Jax got to work. She didn’t just tutor Cody, she taught herself Braille to make her study cards, and made Cody an abacus when she was told she couldn’t have a speaking calculator for the test. Cody went on to pass with flying colors, with some of the highest scores in the prison.

“I’m Not Going to Give Up”

While the work that Poetic Justice is doing is amazing and hopeful – they have reached over 3,000 women in Oklahoma and now California, and they currently serve 15% of Oklahoma’s female prison population, Stackable knows going up against the prison system is an uphill battle. She feels that the correctional system is “fundamentally broken” and “isn’t out there to correct people,” and should be focusing more on dealing with mental health issues and drug rehabilitation, instead of separating women from their children.

As Stackable pointed out, “I think being in prison is really hard, and I think reentering society is really hard..it’s an unusual person who can succeed.” But the women that Stackable and Poetic Justice’s volunteers reach, and who spend those 8 weeks repeating the words “I have a voice, I have hope, I have the power to change” are given “a sense that they matter…and if you can have those 3 things [hope, a voice, a feeling like you can change] when you walk out the door, then you are 10 steps ahead of most people who leave prison. We are not the end all be all for reentry but what we do makes a difference in everything they choose to do. To have a sense that your voice matters and that you are a person of worth and you can express yourself in both writing and speaking, are super powerful. We’ve had input from the parole board, they say when your women come up before us they’re more eloquent than anyone else we talk to.” As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”

As of this writing, Poetic Justice is continuing on, despite restrictions to having volunteers in prisons, and has paired over 300 women (as opposed to the 60 they can reach in-person) with “writing partners” who exchange writing through good old fashioned snail mail. But Stackable is hopeful that they will be reentering prisons for in-person classes soon, although she would like to continue the distance learning aspect. She has discovered that some women are more likely to participate in the remote program because they just wouldn’t feel comfortable in a class setting. “You know, it’s kind of like when you’re in middle school, and you walk into a class and you’re like, oh my gosh, I can’t believe that person’s here! That’s amplified exponentially in prison.”

Feedback for the remote program has been very positive, with the participants making it clear that it has helped with their mental health and has given them the sense that “someone on the outside actually cares about them.” This has been incredibly important over the past year, as, according to Stackable, “They feel more acutely anything happening in the country, they feel a lack of control and wonder ‘Does anyone care about us?’”

The women that Ellen Stackable and Poetic Justice work with know that there are people out there who do care, but, more than that, the program allows them space to explore how they can care for themselves. And whatever happens, Stackable is going to keep going and keep making a difference, despite what can seem like insurmountable odds. “I think about the people that I love on the inside [of prison], I have a couple that call me every week, you know I just can’t go too much into all that is broken or I would give up. And I’m not going to give up.” If you want to help, go to Poetic Justice’s website, and consider providing a scholarship to one of their participants.