Going to the doctor for a checkup can mean being bombarded with numbers. Your cholesterol levels, blood pressure, heart rate – not to mention, some people’s least favorite number to get thrown at them: that little digital number staring back at them from the scale. But it doesn’t end there: your doctor will then use your weight to calculate what is known as your body mass index, or BMI, which is a measure of your body fat based on your height and your weight.

This number might say a lot to your doctor about your health status, and determine a lot about the care you receive. It can even be used when determining things like your life insurance rates! But is a simple calculation of your height and your weight really enough to say so much about your health? A lot of experts say no, especially since BMI has a problematic history, and can be racially and gender-biased. So how can a number be biased? Let’s take a look.

What Is BMI?

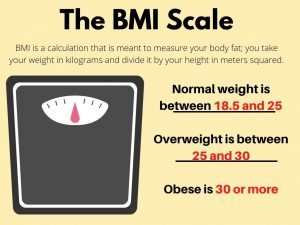

How is your BMI calculated and what does it supposedly mean? Your body mass index is a calculation that is meant to measure your body fat; to figure it out, you take your weight in kilograms and divide it by your height in meters squared. That number will determine whether you are considered underweight, normal weight, or obese. You are considered:

- Normal weight if your BMI is between 18.5 and 25

- Overweight if it is between 25 and 30

- Obese if you have a BMI of 30 or more

This system might sound a little too simplistic and cookie-cutter to give an accurate picture of your body composition. And in fact, it was designed to be simple. BMI was devised in the 1830s by Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet (1796-1874), a Belgian mathematician, sociologist, statistician, and astronomer, and during Quetelet’s time there were no calculators, computers or electronic devices, which is probably why he opted for a super-simple system.

But we’ve obviously moved on in terms of diagnostics in many ways since then, and we have a lot more technology at our fingertips, so is BMI still the best way to determine how healthy we are, and to assess our health risks? Many experts say no, especially since the one-size-fits-all (no pun intended) nature of BMI can be very problematic.

BMI’s Problematic History

Here’s the thing about the history of BMI, or rather, here are two things: first, Quetelet did not intend his “Quetelet Index” to be used for individuals; it was meant to be a population-level tool. Second, this tool was developed using data from predominantly European men – and almost no study today conducted on one ethnicity or gender would be considered accurate if applied to people outside of those groups.

But still, physiologist Ancel Keys reintroduced the calculation in 1972, because he was irritated that life insurance companies were estimating people’s body fat (and so, their risk of dying) by comparing their weights with the average weights of others of the same height, age, and gender. So he conducted a study of more than 7,000 healthy, mostly middle-aged men, and found that body mass index was a more accurate predictor of body fat than the method that was being used by life insurance companies. The Quetelet Index was thus rebranded as BMI, and it has since been adopted by the medical community as a way to measure individual health. And the rest is history: we are now told that a BMI outside the “normal” range (18.5-25) is considered less healthy, and an indicator of greater health risks.

Taking all of this history of BMI into account, critics are now pointing out that this measure of body fat, and ultimately health, is not just unreliable, but also racist and sexist. According to Sabrina Strings, an assistant professor at the University of California, Irvine, “It is racist, and also sexist, to use mostly white men within your study population and then try to extrapolate that and create norms and expectations for women and people of color. They have not been included in the initial clinical analyses, and therefore their actual health outcomes cannot be determined by these findings.”

Not only that, but the development of BMI as a health marker is also actually rooted in racist ideas that upheld certain northern and western European bodies as the ideal, bodies that tended to be thinner than those of eastern and southern Europeans, as well as Africans and people from other parts of the world. That means that it’s very easy for people who aren’t in that “ideal” category to be viewed as “inferior,” just because of one simple calculation.

In addition, BMI was created when there wasn’t much understanding of the relationship between health and weight – something we’re still trying to figure out. For example, some experts point to other cultures who tend to have higher BMIs, but better health outcomes than some Western populations. So with all of these problems with BMI, why do we still place so much importance on it, and how does that importance affect our everyday lives?

How BMI’s Bias Can Affect Care

Just how does the fact that BMI is unreliable, and even racist and sexist, affect people in the real world? Well, first of all, some experts think it’s really not an accurate measure of health: according to Jennifer Gaudiani, an internal medicine physician and certified eating disorder specialist based in Denver, Colorado, “We cannot use weight as a marker of health. It just does not correlate, except on the very extremes.” She thinks that being a certain weight doesn’t necessarily make you healthy or unhealthy.

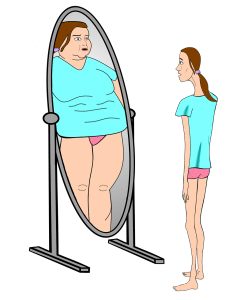

In fact, things like eating disorders or even tumors can be missed because someone is considered “overweight” based on their BMI. Or consider this: someone might reach a weight that makes them healthy and happy, but still fall outside of the “normal” BMI category, and feel pressured to unnecessarily and unrealistically drop even more weight. And, on the other hand, doctors can also assume that someone is healthy simply because their BMI is in the “normal” range.

Dr. Yoni Freedhoff, an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa, agrees, pointing out that body mass index, which was created as a way to look at groups of people, is “fairly useless when looking at the individual.” It might work to track risks or trends across large populations, but it doesn’t say much about an individual’s actual body composition (muscles vs. bone vs. fat), which means it puts people with more muscle in a higher category. BMI also won’t change if a person’s body composition changes, which could mean missing potential serious health issues.

To put a finer point on the unreliableness of BMI, a 2016 study of more than 40,000 adults in the United States found that it was a pretty poor predictor of metabolic health. Researchers compared people’s BMIs with more specific measurements of their health, like their insulin resistance, markers of inflammation and blood pressure, triglyceride, cholesterol and glucose levels, and found that nearly half of those classified as overweight and about a quarter of those classified as obese were metabolically healthy by these measures. On the other hand, 31% of those with a “normal” body mass index were metabolically unhealthy.

So, a large percentage of our population is being labeled as “not normal,” and thus not healthy, which can be extremely damaging. Experts like Gaudiani point out that using BMI as an important marker of health can create multiple types of vicious cycles, especially in underrepresented populations. For example, a young girl of color might go to a pediatrician at age 7 or 8 and be told that they’re overweight, when in fact they’re just experiencing a normal prepubescent weight surge earlier than a young white girl might. Hearing this at such an early age can put them on track to suffer from mental and physical health issues related to body consciousness and fear that they’re body isn’t “right” or healthy.

To give another example of a vicious BMI cycle: issues that are more prevalent in minority communities – discrimination, lack of access to care, poverty, and even stress – can lead to higher BMIs in those populations, and that in turn can lead to even worse care from the medical community. Doctors can end up focusing solely on a patient’s BMI, and want to discuss their weight before they get to the concerns that brought them to the doctor in the first place. That means legitimate medical concerns that have nothing to do with weight might go neglected, and the patient might even choose not to seek further care, because they end up feeling stigmatized.

According to Lesley Williams, a family medicine physician and certified eating disorder specialist based in Phoenix, Arizona, “I hear time and time again, ‘My physician wouldn’t listen to me. I had this myriad of complaints that had nothing to do with my weight, and all they wanted to do was talk about my weight, and I was not being served, and I’ve just elected not to go back.’”

All of this means that discrimination and lack of access to quality medical care can affect BMI, and they can also simultaneously be the result of a higher BMI, creating an endless cycle. In fact, people who have felt discriminated against because of heavier weight are around 2.5 times more likely to have mood or anxiety disorders, and are more likely to gain weight and have a shorter life expectancy. And the really crazy part? Evidence suggests that having a higher BMI is not even clearly linked to earlier death in minority populations. So it seems that it is much more important that we address the structural factors that lead to poor health, like “poverty, racism, lack of access to healthy fruits and vegetables” and environmental toxins, according to Dr. Strings.

Is There an Alternative?

So with only about a quarter of the U.S. population considered “normal” on the BMI scale, what would be more helpful than focusing on these numbers? Again, it is really important that we focus on the structural things, but that is obviously the long game. Until then, we can use other markers for health, and not focus so much on weight. If you are worried about your weight, though, it might be more helpful to have your doctor monitor your waist size, which could be a better indicator of how much dangerous abdominal fat you have.

But, for doctors who are ditching the BMI as a reliable or helpful tool, it’s more important that they look at the bigger picture of their patients’ health. For example, rather than focusing on body size as a gauge of health, your blood glucose, triglyceride, and blood pressure results can be better windows into your well-being.

How you feel in your body is important, too. In fact, some doctors, like Dr. Freedhoff, “discuss something we call ‘best weight,’ which is whatever weight a person reaches when they’re living the healthiest life they can actually enjoy.” A. Janet Tomiyama, an associate professor of health psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, agrees, asking simply “Can you go up a flight of stairs and feel good about how you feel after that? How are you able to live your life in the body that you have?”

So being your “best weight,” in conjunction with prioritizing behaviors that are more within your control than your body mass index like, according to Dr. Tomiyama, “better sleep, more exercise, getting a handle on stress and eating more fruits and vegetables” will go a much longer way to making a difference in our lives than a number based on an outdated and biased scale.